Chasing Ghosts

Chasing Ghosts

In the middle of the Indian Ocean lies a vast archipelago spanning over 870 km, comprising 26 atolls and approximately 1,200 islands. This country has always been a bucket list travel destination due to its luxury resorts, stunning beaches, and breathtaking reefs. This is the Maldives. In June of 2022, I was hired to work for The Ritz-Carlton Fari Islands in North Male Atoll. My job title was the Naturalist for the resort, and I was responsible for the conservation projects, scientific communication, guest engagement, and guiding snorkeling and scuba diving excursions. For two years, I was incredibly fortunate to work at a Forbes 5-Star resort, where I encountered a wide array of marine life while performing my duties. The Maldives is a stunning country with abundant marine biodiversity. The Atolls formed millions of years ago from volcanoes emerging from the depths, then dying and sinking, leaving a ring that allowed coral reefs to form. In the ever-empty abyss of the ocean, this place is an oasis for marine life.

Marine Threat

Unfortunately, this oasis is under threat in the Maldives and worldwide. Marine life globally is declining due to various human-related factors, including ocean warming, acidification caused by chemicals and waste, and industrial overfishing. However, there is a silent killer that is not talked about that paves a highway of destruction wherever it goes. Conservationists and marine scientists use the term “Ghost Nets” for this silent killer. A ghost net is a fishing net or FAD that has been either purposely lost or accidentally abandoned at sea. FAD stands for Fish Aggregation Device, which is a bunch of material, for example, like a large rope that can have trees, cloth, plastics, palm fronds, rope, and other rubbish tied to it. The ocean is an extraordinary creator of life, so when something like an FAD is in the water, biomaterial begins to form, attracting smaller marine life and game fish that fishermen want to catch. Unfortunately, if a turtle gets caught in a net or FAD, when it dies, it attracts other predators. So, then a shark will try to eat it, and, unfortunately, it gets caught. This never-ending cycle of destruction is truly one of the most damaging things occurring in our oceans. The WWF estimates that around 500,000 to 1 million tons of ghost net gear goes into the ocean annually. A report by the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) estimates that ghost nets kill approximately 650,000 marine animals annually.

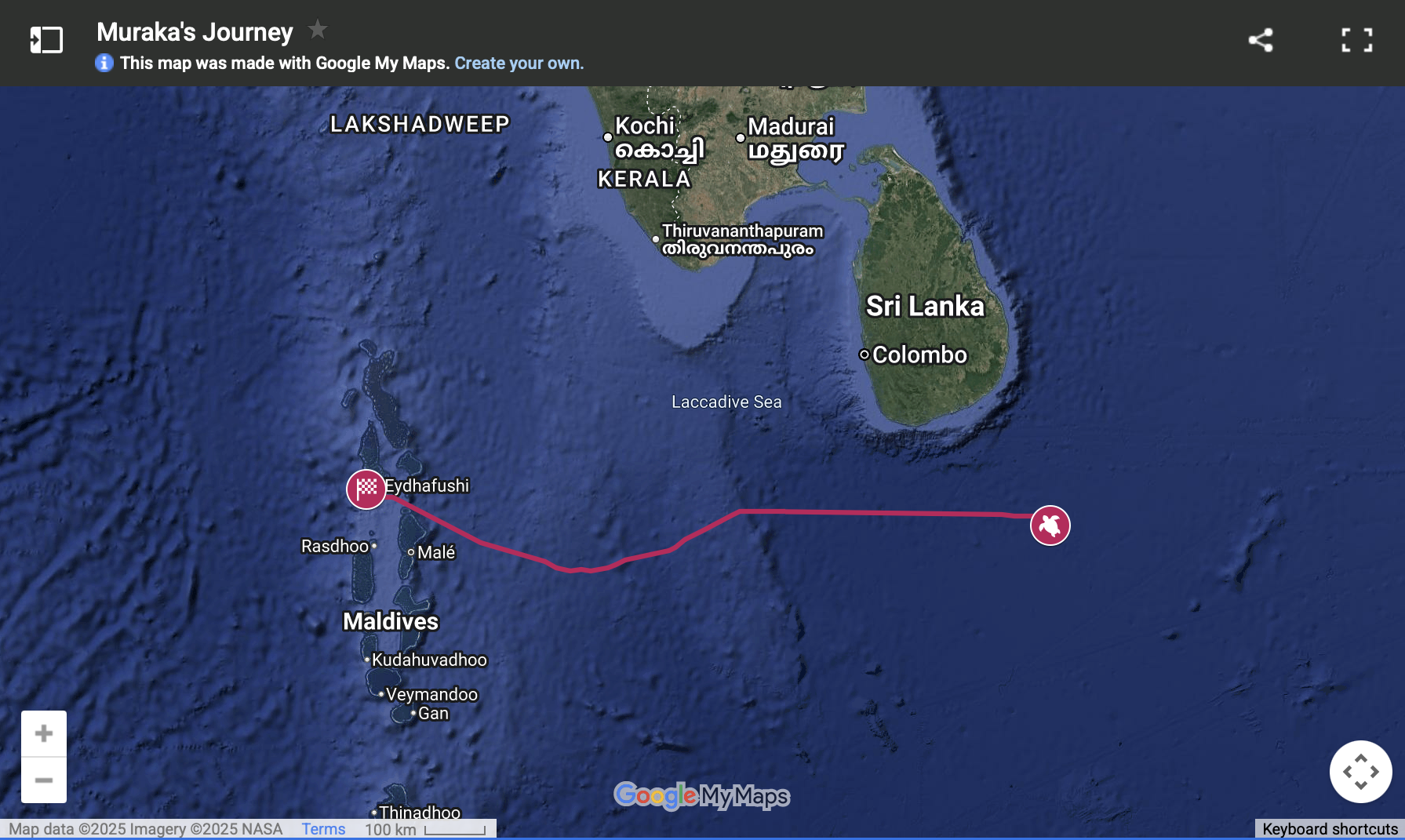

The Maldives, located in the middle of the Indian Ocean, are surrounded by countries with some of the worst regulations regarding sustainable fishing. To the west of the Maldives are Somalia and Yemen. India and Pakistan are to the northeast, and to the east are Sri Lanka and Indonesia. There are amazing conservation efforts in some of these countries, but there is also a high demand for fish, primarily tuna. The ghost nets from all these countries accumulate in the Maldives. They come from the east or the west, depending on the time of year. At the Ritz-Carlton, my work included monitoring this destructive phenomenon, and we were the first resort in the country to use drones to study the movements of ghost nets.

Melissa’s Work

This amazing project could not have been accomplished without the talented, passionate, and driven Dr. Melissa Duncan-Schiele. She is one of the most intelligent and incredible scientists I have met and worked with so far in my career. She serves as an inspiration to individuals in the STEM field, particularly women aspiring to enter STEM careers. Melissa built her drones, which were water-landing remote-controlled planes, and deployed them primarily in the Chagos Archipelago to study the abundances of sharks and to test the drone as a tool for illegal fishing surveillance. During her PhD, she set up the research projects at the Ritz Carlton, which included ghost net monitoring and plastic detection, as she noticed there was a huge dearth of information on what types of plastic were where, in the Maldives. She established the ‘Ambassadors of the Environment’ program for the Ritz-Carlton Maldives, Fari Islands resort, and worked at the resort in the summer of 2021 during the pre-opening phase. She then became the Sustainability Consultant for the property, until now. Two other amazing naturalists ran the practice before I joined in June of 2022 (Dr Sol Milne and Kat Mason, MSc). The project Melissa set up was to use drones to survey the beaches and ocean area around the resort, then use the images collected and go through them to detect ghost nets hidden from a boater’s perspective. Methods for plastics quantification at resorts will be published soon and presented as a standardized tool for resort workers in the Maldives. Drones are becoming increasingly useful in scientific research, as they are cost-effective and offer a unique perspective when viewing surfaces from above. We created a task force that would go out and remove the nets when we found them entangled in the reef and release any wildlife that was still alive.

Conservation Technology

Drones are cost-effective observation tools for ecology when compared to boat hire, person hire, and fuel costs. This was an important part of why Melissa likes them so much. Melissa’s PhD was in engineering, in conjunction with marine ecology- a natural place for her to discover the world of Conservation Technology. This relatively new research space combines modern field science, tech-savvy scientists, and consumer-grade tech, making field science and research accessible. Scientific gear can be expensive. Think of a satellite tag used on a great white shark to monitor its movements. Some of those can go for 5,000$ USD a tag, and you cannot just tag one animal; you need at least 10 animals to get comparable data. That can become expensive quickly, which then limits who can conduct research, especially in the Global South. With the abundance of electronics at a consumer-grade level, tech-savvy scientists can develop new ways to study animals more cost-effectively. Other conservation technologies include air quality sensors, camera traps, and BRUVs (baited remote underwater videos)- all of which can be cheaply made and deployed.

That is how our project with the drones came to life- to answer a scientific question as efficiently as possible.

Jean-Michael Cousteau

The projects found a home within the Jean-Michael Cousteau ‘Ambassadors of the environment’ program at the resort, and if you know anything about ocean exploration and scuba diving, you know that last name. Jean-Michel is the son of the legendary Jacques-Yves Cousteau. Jacques pioneered the way for ocean exploration. His career began in the French Navy, and he invented the second stage for the first self-contained underwater breathing apparatus in 1943; today, we call that SCUBA. He also developed the first underwater 35mm camera in 1955. In 1962, Jacques was the first person to live underwater in his underwater habitats called Conshelf 1, 2, and 3, which was a crazy exercise to understand what happens due to the extremes the human body goes through at depth. He made many more innovations, but what drew the world's attention to this man was his work in filmmaking, which highlighted the underwater world for people through a television series. The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau used the famous Calypso boat to travel the world. The team on this boat included the world-renowned marine ecologist Dr. Richard Murphy, the scientific advisor for the series. Jacques’ son Jean-Michel also joined these voyages across the world to spread ocean conservation, which led to Jean-Michel Cousteau creating Oceans Future Society in 1999. This organization created the program I worked for at the Ritz-Carlton: The Ambassadors of the Environment. AOTE is a program based at seven different resorts worldwide at the Ritz-Carlton. There is also a resort in Fiji directly owned by Jean-Michel. AOTE aims to engage influential guests of the Ritz-Carlton through conservation education, inspiring them to create policies that benefit our planet.

Ghost Net and Plastics Research

During the week, I would regularly fly the drone. I would record environmental data before flying and spend the flight looking for what was around. I also monitored the wildlife around the islands by drone. My favorite time to fly the drone was before and after work, especially around sunset, as that was when most of the marine life was active. The drone manufacturer DJI has made significant headway in the market by creating reliable consumer drones equipped with high-quality sensors and cameras. We initially used the Phantom 4, but that model became obsolete. Our team currently uses the Mavic 3 Enterprise, which is a powerful drone due to its mapping capabilities. While there, I used the Mavic Mini 3 Pro, a compact drone equipped with an excellent camera. We also collected data on marine plastic and waste, and the survey was conducted over 10 days. I would patrol the beach before the landscaping team cleaned up to count the marine debris that I was able to see and record it. Then, I would fly the drone over the debris to take another look from above. We would then review the data collected by the landscaping team and compare which of our methods detected the most, to determine if drones could be a reliable tool for collecting marine plastic waste data.

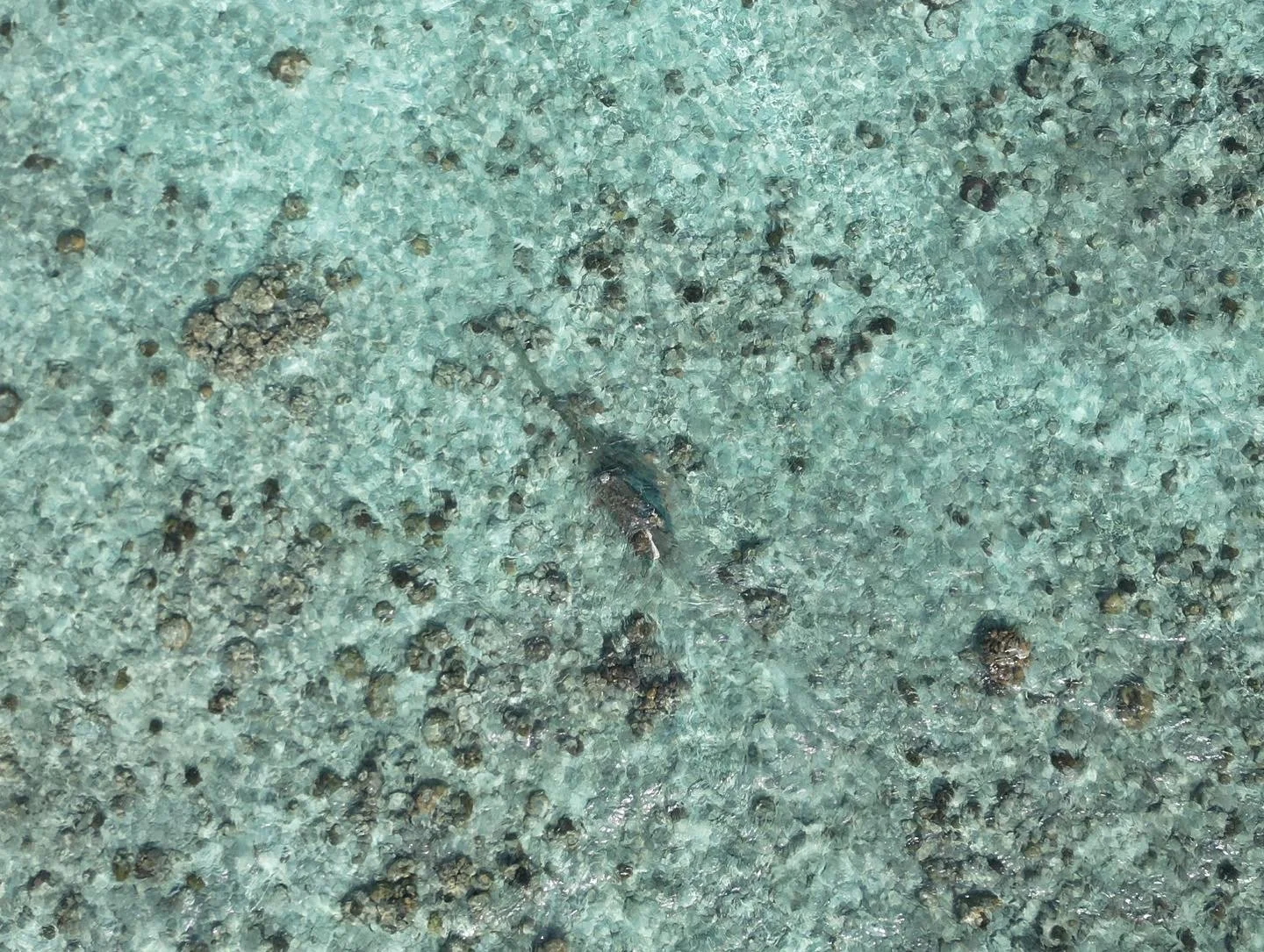

At the resort, with the assistance of the dive team, a dedicated ghost net removal team was established. Ghost nets are difficult to detect from the air by drone. However, we discovered that flying a drone at a low altitude and just the right angle allowed us to see them just beneath the surface. Occasionally, ghost nets were reported to us from dive boats, as drones cannot identify objects at greater depths. Once a ghost net was identified, the process of removal commenced. Then the challenge and fun from my side began. When a ghost net was spotted, I would assess the condition of the net to determine how rapidly we needed to respond. Nets that were physically drifting needed to be taken out as fast as possible, as they could float by, and we would miss them. We promptly attended to nets containing wildlife to enhance the likelihood of survival for entangled animals. Larger nets required more mission planning due to their logistical challenges and the number of divers needed to retrieve them safely and efficiently. The work was tough and required a lot of effort, especially when we were in scuba gear, but it was worth it to get them out of the water and halt their path of destruction. The most common months for nets were January to April, when the winds came from the east, as the Ritz-Carlton was on the eastern side of the atoll. North Male Atoll is on the east side of the country, and this area gets the most nets, as this is the first land mass with which they come in contact. There was less ghost net activity from May to October, when the winds were from the west, pushing the nets onto other atolls. The east winds also brought in saltwater crocodiles, as they get blown in from Sri Lanka, which is not what you expect to find in the Maldives! However, that was exceedingly rare; only a few individuals showed up each year. A crocodile was spotted 25 minutes by boat from the resort, at a location where ghost nets had been removed. There were no encounters with crocodiles at the resort itself.

Ghost Net Retrievals

Turtle Rescue

My first turtle rescue is something I will never forget. I was flying my drone early in the morning and going around the barrier reef near the west side of Fari Island. I noticed a long streak on the ground, like someone had used a paintbrush across the sand. For surveys, I flew the drone around 70 meters above the surface of the water, so I dropped the drone down to inspect what I saw, and just under the water was a ghost net caught in the reef. I sent a message to our Ghost Net Rescue team. My coworker Daia, my friend Mike, and Rameez, the lifeguard who operated the boat, arrived on the scene. Since the net was underwater, I used my drone to guide them to the net. I was taking photos of them getting the net out, but it was taking longer than usual. Then Rameez phoned me and told me a turtle was stuck in the net. They also found the remains of another turtle. I immediately got in touch with the Olive Ridley Project (a UK-based charity) that takes in injured turtles around the Maldives and rehabilitates them. The boat returned with the net and the turtle. We discarded the net, and then I gave my attention to the sea turtle. The ORP is based at the Coco Resort in Baa Atoll, so we would have to get this turtle out on a float plane. Luckily, there is an agreement in the country that turtles are free to fly. While we can care for turtles here, we do not have the water tanks to hold a sea turtle, so the ORP reached out to their colleague at the One & Only resort. When we arrived, I handed it over to the turtle caretaker, and the turtle was transported to the clinic the next day, where the vets could provide it with the care it needed. We named the turtle Fari since we are in the Fari Islands. The name Fari means beautiful in the local language. Olive Ridley turtles are pelagic and rarely come close to shore, except during nesting season. Their diet is diverse, including jellyfish, algae, mussels, and fish. However, they often encounter ghost nets in the open ocean, making them among the most common species entangled in nets around the Maldives.

Other Rescues

While I was on a trip in the south Maldives, diving with tiger sharks, Daia had to respond to a ghost net her team found, with two olive ridley sea turtles stuck in it. The dive boat and five others took this one back to our jetty and pulled it out of the water. The net weighed around 350kg.

Sometimes we don’t make it in time, and unfortunelty a turtle drifts so far and is caught where they cant breath, like this individual

Boat Strike

FADS

Before my time at the resort, the largest Ghost Net/ FAD removed was a gigantic FAD. This agitation device had a large metal bell attached to keep it afloat. There was about 60 meters of rope, and the rope near the top was thick. Then, they had tied many other pieces of rope and junk to the rope to allow for a larger surface area for the biomaterials to attach. Dr. Sol and Kat, the naturalists at the resort before me, found it. They were notified of a gigantic FAD stuck on one of the little thilas (submerged pinnacles) where we would take our hotel guests. They got the team together, but it would be a difficult dive to handle this one. The team managed to pull the largest part of the FAD up by cutting it into sections. A portion of it was left at the bottom because that section was in water deeper than 30 meters.

During our shark research with Gibbs Kuguru and Walker Nambu from Wageningen University and National Geographic, the dive team spotted a FAD on the outer reef. Walker, Mike, and I went out on the zodiac to try to remove it. This was an illegal one, as some are legal, but those typically have GPS trackers that the fishermen use. This one had lots of palm fronds and plastic bottles all tied together. We removed the FAD, and as we pulled it out of the water, I spotted what appeared to be a shark egg. I set the egg upon my hand, and the baby hatched right there! I released it directly into the water. After researching the shark species, it turned out to be a type of bamboo catshark. This species is found on the eastern side of India. This is one of the unique things we can discover from ghost nets. We can identify the origin of where that ghost net was first laid by identifying the species that are found in the nets. This one was likely from India or Bangladesh. This also demonstrates how ghost nets can transfer invasive species worldwide, which negatively affects local flora and fauna.

Reef clean-ups

We found numerous smaller nets using the drone on the outer reefs surrounding the resort. Smaller pieces of net get caught in the reefs, and a full-on team was not required to extract them. We would do a big dive at least once a month to clean up the reefs around the resort. The most common thing we would find on our clean-up dives was fishing line. Unfortunately, it is easier for the fishermen to cut the entangled line and throw in a new one.

I would love to pitch a documentary to Netflix, created by the same team behind Chasing Ice and Chasing Coral, titled ‘Chasing Ghosts’, which highlights the destruction caused by ghost nets. It would feature the hardworking and amazing conservationists and marine scientists who are tackling this massive issue in our oceans and give them the recognition they deserve.

Acknowledgments

This incredible work would not have been possible without the amazing support from the Ritz-Carlton Fari Islands and Dive Butler International. I am especially grateful to the wonderful individuals who made this journey even more special: Melissa, Juliana, Mike, Daia, Luca, Shafiu, Maria, Shifan, Haneef, Mohammed, Sol, Kat, Zimmam, Tahey, Amyn, Saamu, Canan, Dzerasse, Arianan, Fabian, and Judith. Thank you all for your help, and stay wild!